My boss has been away for a couple of weeks. I’m in that weird limbo between the completion of a project and the beginning of another one. Uncertain about what to do next and somewhat bored to even start thinking. I figured that all I needed was some good old ego boost. Didn’t turn out as I thought.

The community of physicists to which I belong, high energy physics, is somewhat small and peculiar. Our job is to develop new ideas and write papers about them. The new ideas we try to develop are about Nature, trying to understand and explain the way it works at the most fundamental level.

The papers we write are usually published on scientific journals like in any other scientific field. What is peculiar about high energy physics is that nobody really cares about scientific journals and to make our ideas immediately accessible as they come to final form, the arXiv was created (at the beginning of the nineties). When a paper of mine is ready I would just post it on the arXiv for anybody to read it. For free.

The arXiv is divided in many categories depending on the discipline. All my papers are in two of them hep-ph and hep-th, standing for High Energy Physics - Phenomenology and Theory.

The arXiv did not exist when Steven Weinberg wrote his most cited and Nobel worth paper, A Model of Leptons, so you will not find it there. Luckily there is another online tool which is bread and butter for high energy physicists, which allows you to search for every single paper ever written by the community. This is the INSPIRE database.

INSPIRE periodically uploads a screenshot of the whole high energy physics production (and more) in XML form. Every paper and author is assigned a unique identifier. The database contains information about each paper, like title, abstract, date of appearance, arXiv identifier (if it applies), and so on. An almost complete description of the database can be found here.

So my plan: download the INSPIRE database and compare various bibliographical indices for the high energy physicist of my generation. Possibly turn out to be a freaking boss.

Reading the database

Two files are relevant for our purposes, they are HEP and HepNames, the first containing records of papers and the second records of authors, both with their unique ID.

The first problem to face is the size of the HEP file, something short of 18 GB. Simply reading it into memory is out of the question as it would annihilate my laptop. One possibility is to be somewhat clever and use libraries like ElementTree to parse the XML. I ain’t got no time to learn all that. One very efficient brute force approach is to parse the XML file like a normal text file and save the relevant information from each record, without overloading your memory.

rec = ''

with open('HEP-records.xml','rb') as f:

flag = False

for line in f:

if '<record>' in line:

rec = line

flag = True

elif '</record>'in line:

rec += line

flag = False

process_record(rec)

del rec

elif append:

rec += line

The previous loop reads the content of the XML between two <record> tags and calls the function process_record on it. This function now has to deal with a very small chunk of the original XML file and extract the relevant info from it. For instance

import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET

def process_record(rec):

chunk = ET.fromstring(rec)

item=chunk.findall("./controlfield[@tag='001']")

dictionary = {'item': item}

append_record(dictionary)

In this case the 001 tag read the unique INSPIRE ID for the paper. Many more fields have to be recorded for the analysis. The function append_record finally append the dictionary to a file (again without having to load the whole thing in memory)

import os

def append_record(dictionary):

with open('INSPIRE', 'a') as f:

json.dump(dictionary, f)

f.write(os.linesep)

The resulting file is in JSON style but it is not a JSON yet, it has to be properly wrapped, but that’s easy.

with open('INSPIRE') as f:

list = [json.loads(line) for line in f]

with open('INSPIRE.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(list, f)

The full codes to read both the HEP and the HepNames database will be uploaded on my GitHub. I will also upload a reduced version of the HEP database itself. It is a snapshot of INSPIRE at the time this post was written, so it can get old.

The field which are relevant for the bibliographic analyisis are the following. From HEP

item=chunk.findall("./controlfield[@tag='001']") # ID

cat=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='037']/subfield[@code='c']") # arXiv category

date=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='269']/subfield[@code='c']") # date of appearance

aut1=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='100']/subfield[@code='x']") # first author ID

aut2=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='700']/subfield[@code='x']") # other authors ID

refs=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='999'][@ind1='C'][@ind2='5']/subfield[@code='0']") # list of references

and from HepNames

item_aut=chunk.findall("./controlfield[@tag='001']") # ID

name=chunk.findall("./datafield[@tag='100']/subfield[@code='a']") #author name

The resulting tables can be read in as pandas dataframes.

import pandas as pd

data_HEP=pd.read_json('INSPIRE')

data_names=pd.read_json('HEPNAMES.json')

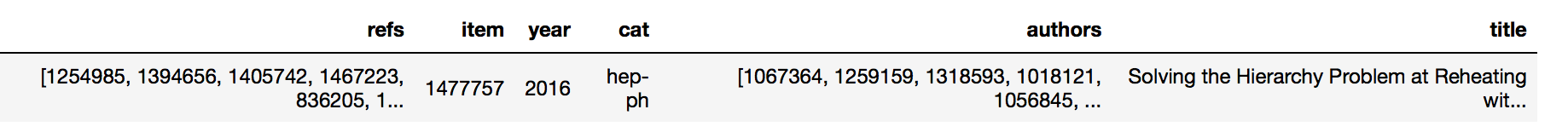

This is the way one HEP record looks.

I joined the field aut1 and aut2 into the new field authors and extracted a field year from date.

The analysis

Now the various simplifications for the analysis. I am interested in comparing my bibliographical record with that of authors active in my field and belonging to my same generation. I published my first paper in the second half of the noughties. All my papers are sent to the arXiv before they are pubished on a journal and this is pretty common for people in my field. More specifically all my papers appear on the hep-ph and hep-th categories of the arXiv.

I will thus rate authors in terms of papers they wrote on hep-ph and hep-th. I will furthermore restrict to those who published their first paper on hep-ph and hep-th no earlier than 2006.

The arXiv category of a paper can be selected according to the cat field

data_HEP=data[data['cat2_'].isin(['hep-ph','hep-th'])]

In order to enforce the time requirement I define a list of unique authors as

temp=data_HEP['authors'].tolist()

unique_authors = [item for sublist in temp for item in sublist]

unique_authors = set(unique_authors)

I then define ‘old’ authors as those having a paper before 2006, and ‘young’ authors as the rest

data_HEP_old=data_HEP[data_HEP['year0_']<2006]

temp=data_HEP_old['authors_'].tolist()

unique_authors_old = [item for sublist in temp for item in sublist]

unique_authors_old = set(unique_authors_old)

unique_authors_young = [x for x in unique_authors if x not in unique_authors_old]

The number of young authors so defined is 10983. I also define data_HEP_young as the subset of hep-ph/th papers written by at least one ‘young’ author. The number of such papers is 42612.

So some disclaimer. If you are reading this and your most cited paper appeared on astro-ph, well, it will not be counted. Similarly if you belong to a big experimental collaboration but you are also a theorist, your 1000+ papers from CMS will not be counted. Also, give a 10% error margin to all the numbers I will quote. And don’t get mad at me.

Notice however that ALL paper of the INSPIRE database will be considered for citations. So if your paper written on hep-ph had impact on some other field like hep-ex or astro-ph, this will matter.

Results

The first thing one can do is to associate to every ‘young’ author the number of paper he/she wrote. This can be done with a simple list comprehension counting how many times each young author appears among the entries of data_HEP_young['authors'].

from collections import Counter

authorship_young=data_HEP_young['authors'].tolist()

authorship_young=[item for sublist in authorship_young for item in sublist]

authorship_count_young=Counter(authorship_young)

data_authors=pd.Series(unique_authors_young).to_frame(name='authorID')

num_papers=[authorship_count_young[str(l)] for l in unique_authors_young]

data_authors= data_authors.assign(n_papers=pd.Series(num_papers).values)

map_names=pd.Series(data_names.name.values,index=data_names.item_aut).to_dict() #Add name

data_authors['name']=data_authors['authorID'].map(map_names)

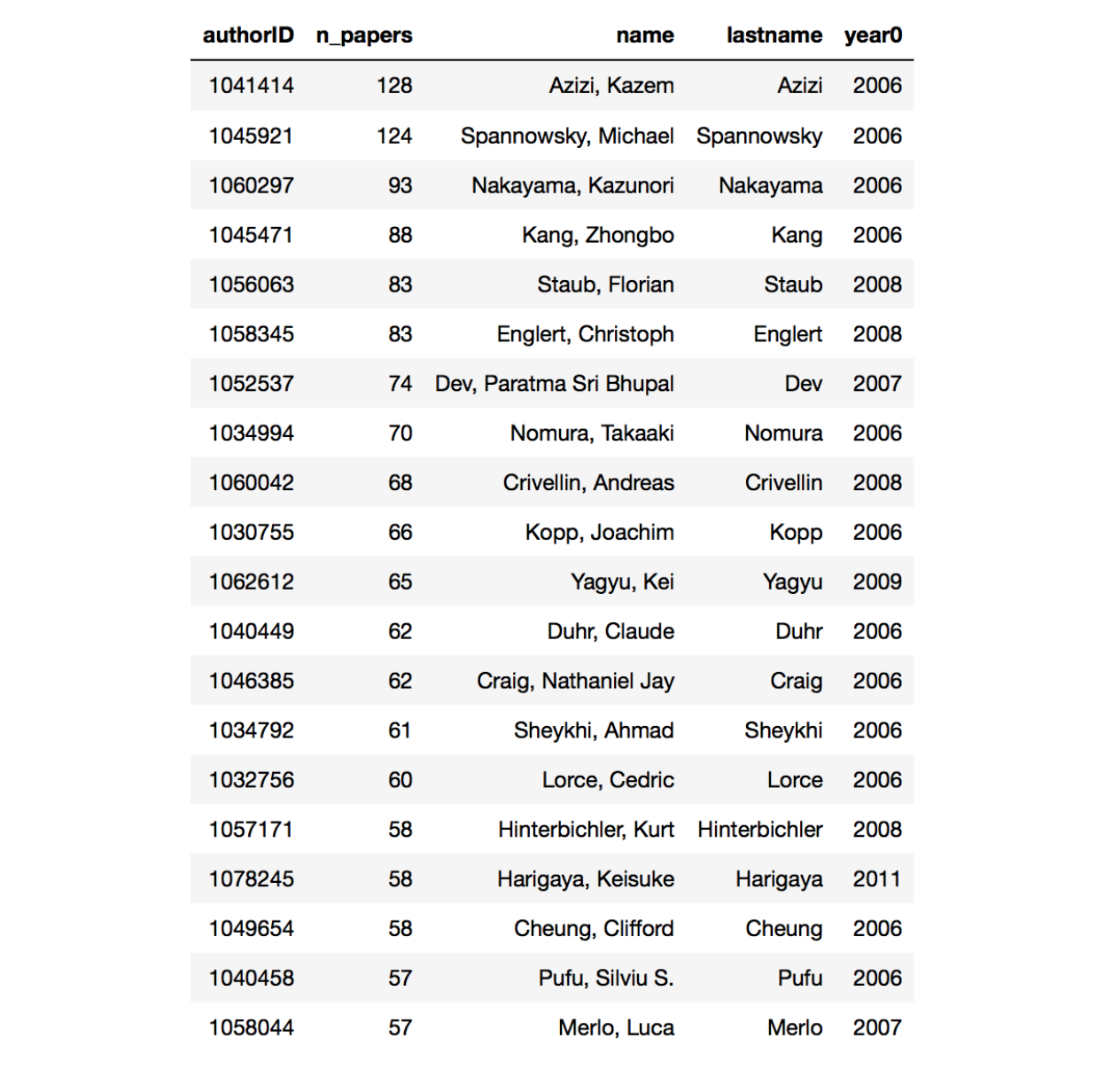

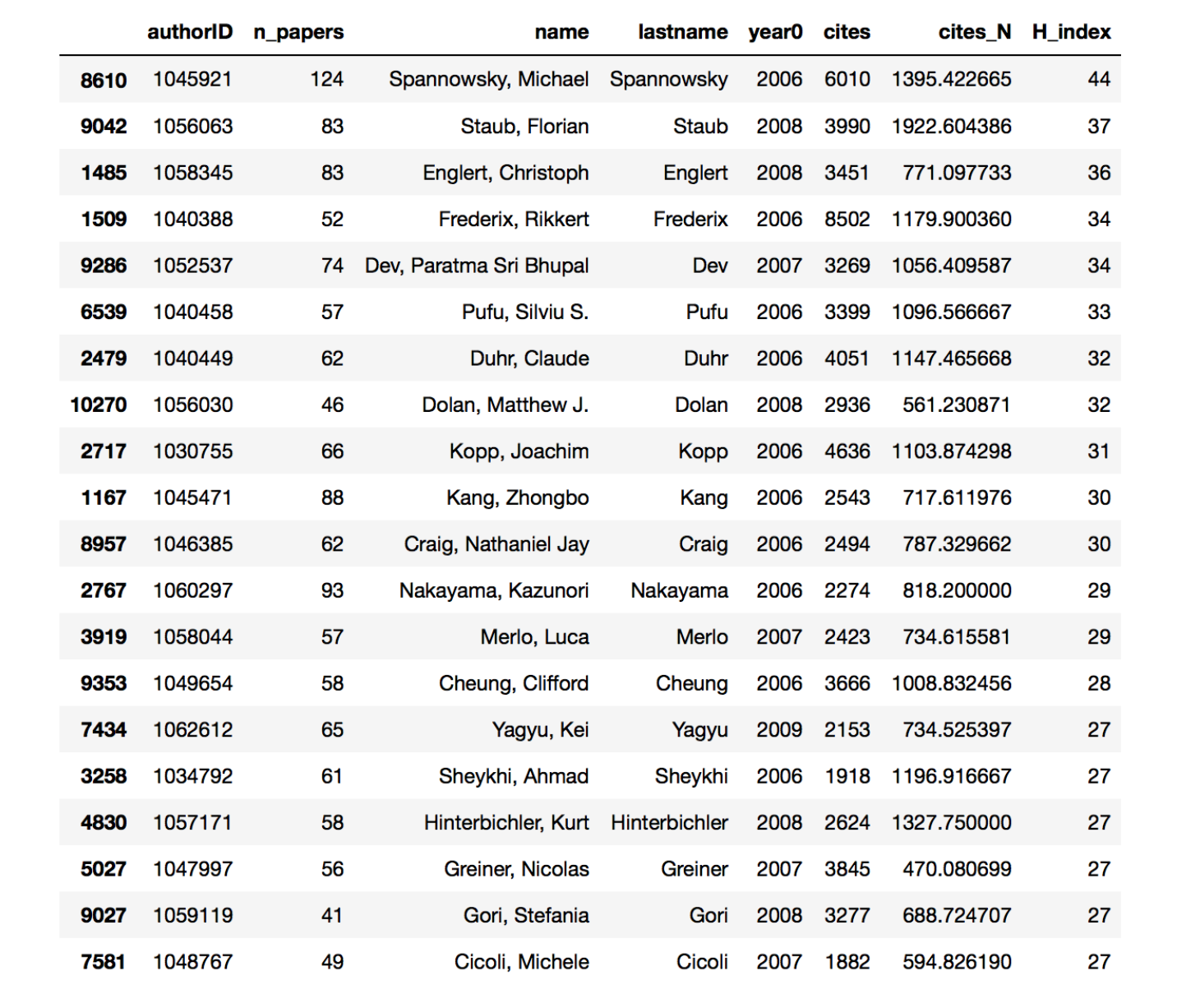

This is the result ordered py n_paper. The field year0 show the year the first paper was published.

DANG! Considering that this does not even include all papers, the first two authors wrote roughly 12 papers per year. I have to say that while the first author publishes on hep-ph, his paper are typically dealing with nuclear physics problems. The second author on the other hand is a full fledged phenomenologist. Also you may notice that the first ten or so authors all publish mainly on hep-ph. Just to keep it real: my score on this table is 29 papers in 10 years. Kinda sad.

Let’s now add the total number of citations each author got. The number of citation per paper can be obtained in the same way we obtained the number of papers per authors. We also care about the number of citations per paper normalized to the number of authors. This should somehow distribute citations according to the amount of work performed by every single author. We thus define two new fields in data_HEP_young, cites and cites_N. We then associate the sum of citations and its normalized sum to every young author. To do this we unroll the relevant columns of data_HEP_young:

data_cites=data_HEP_young[['authors','cites','cites_N']]

temp = data_cites.authors.apply(pd.Series).unstack()

data_cites = data_cites.join(pd.DataFrame(temp.reset_index(level=0, drop=True)))

data_cites.rename(columns={0: 'author_'}, inplace=True)

data_cites.dropna(subset=['author_'], inplace=True)

data_cites = data_cites.drop('authors', 1)

We then group according to the column author_, sum and attach a new column to data_authors:

cites_series=data_cites.groupby('author_')['cites'].sum()[data_authors['authorID']]

data_authors= data_authors.assign(cites=pd.Series(cites_series.tolist()).values)

cites_N_series=data_cites.groupby('author_')['cites_N'].sum()[data_authors['authorID']]

data_authors= data_authors.assign(cites_N=pd.Series(cites_N_series.tolist()).values)

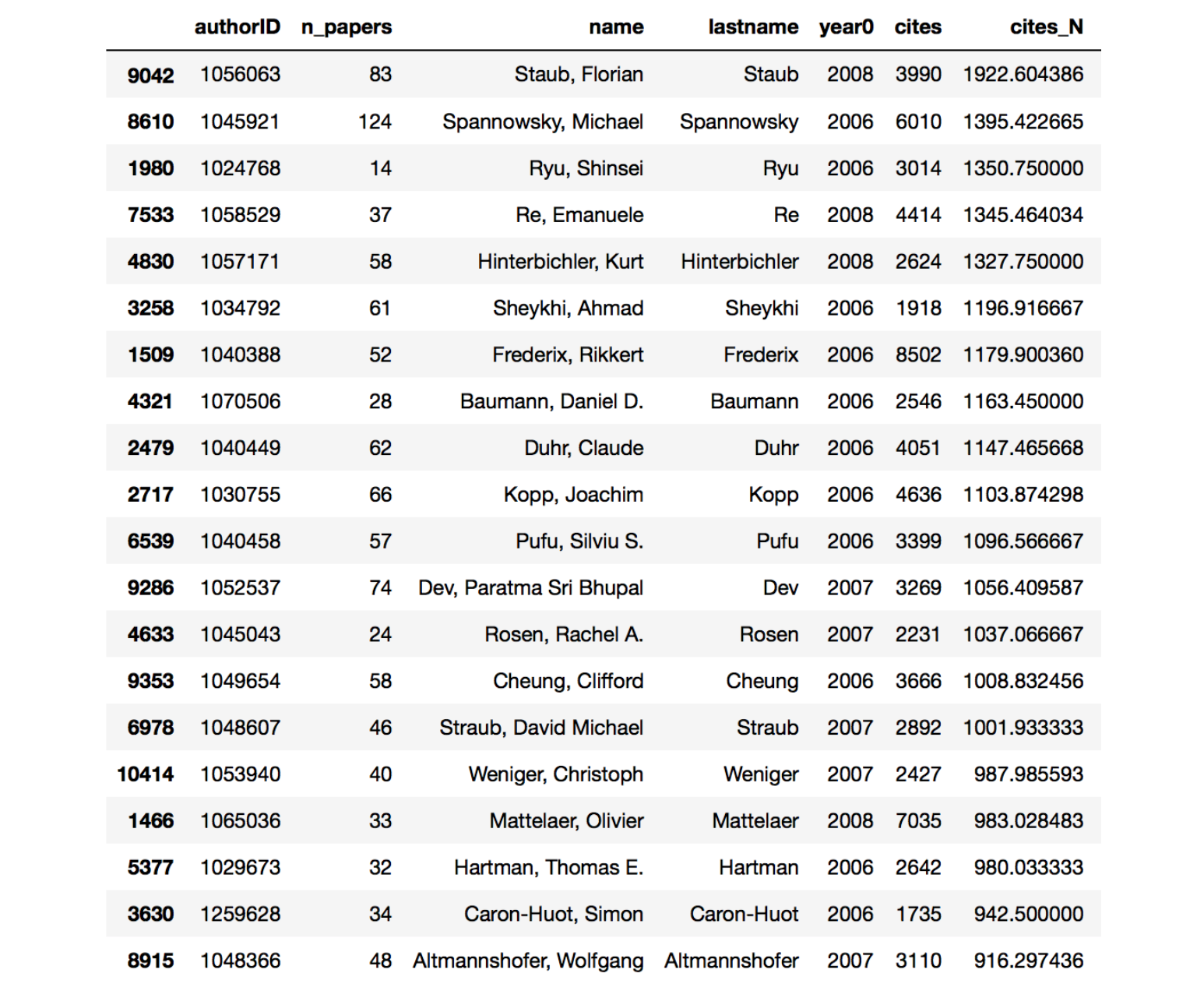

And these are the results, first 20 ordered by cites.

Many of the authors that end up at the top of the chart now are people working in developing numerical tools for QCD calculations and collider studies. These tools are widely used by the hep-ph and hep-ex communities and lots of citations ensue. Ordering by cites_N things change a little bit, in particular many more hep-th people pop up.

The h-index

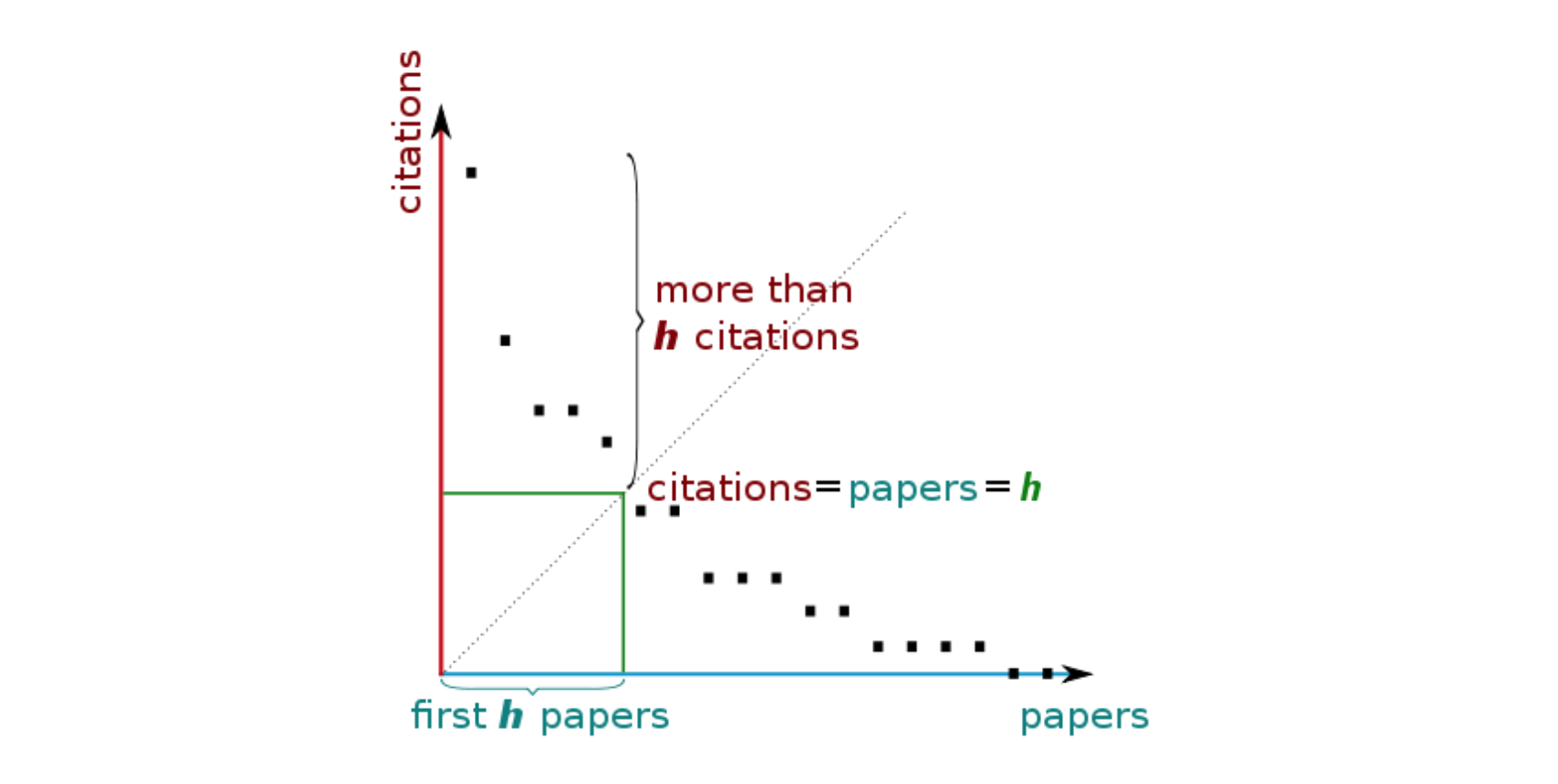

One widely used bibliographical index is the so called h-index. Your h-index is the largest number N for which the following condition apply: you have at least N papers each of which has N citations or more. Here is a little schematic from Wikipedia

Given an author and the list citations of the number of citations of his papers, the h-index can be calculated like this

def hIndex(citations):

citations.sort(reverse=True)

return max([min(k+1, v) for k,v in enumerate(citations)]) if citations else 0

You can start to get used to some of the first entries in these lists. Just for comparison, my h-index comes out to be 19. I am within the first 150 authors. Not impressive. Could be worse.

PageRank

The last index I will consider is PageRank. This is one of algorithm Google itself uses to rank websites. Page in PageRank comes from the lastname of one of its inventors, Larry Page. The possibility to use PageRank to rank papers (and authors) comes from the fact that the set of papers can be understood as an oriented graph. Given two papers a and b, a->b if a refers to b.

Given such a graph, PageRank calculates the probability that a long random walk leads to a specific node. In order to calculate the final probability one has to specify one parameter alpha (ranging between 0 and 1), which is the probability that an user will decide to continue to look at any of the references of a given paper.

The possible advantage of PageRank with respect to ordinary bibliographical indices comes from the fact that a paper may have few citations but its PageRank importance will be high if it is cited by a paper with large PageRank and not too many references.

The larger alpha is, the larger the importance of long chains of citations will be.

Notice that a healthy citation graph is acyclic, that is it does not contain closed loop. In reality some of the papers on INSPIRE can reference paper in the future. I will not try to correct for these effects as they are assumed to represent a small deformation.

By definition, the sum of PageRank for all the papers on INSPIRE will be one. Since I am interested to look at papers on data_HEP_young, I will normalize the scores so that the sum of PageRank on data_HEP_young is 1. In order to rate authors according to the PageRank of their papers, I will assign to every author the sum of the PageRank of his/her papers normalized by the number of authors.

Now we only have to calculate these numbers. In principle all it takes is to invert a big matrix, whose dimension is given by the number of papers. This is clearly impossible with 1 million+ papers. Recursive algorithms are obviously available. Again, I don’t want to spend too much time in testing them, nor I want to write my own version of PageRank in Python. Luckily [Mathematica] has its own function, PageRankCentrality, which is able to calculate the PageRank for a huge graph in a matter of second. All it needs is a graph and a value for alpha.

In order to get the INSPIRE citation graph in Mathematica I save the relevant information to build it on a JSON file cit_graph.json. It will contain the list of papers ID and the associated references.

list_item=data_HEP['item'].tolist()

list_item_U=[unicode(i) for i in list_item]

list_cit=data_HEP['refs'].tolist()

cit_graph=dict(zip(list_item_U,list_cit))

with open('cit_graph.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(cit_graph, f)

Now open Mathematica. After reading the file jsongraph = Import["cit_graph.json", "JSON"], one has to build the graph according to Mathematica format. This can be done with the function Graph which takes a list of nodes and a list of edges, returning a graph. The edges have to be specified by the function DirectedEdge, which takes two vertices and return the directed edge between the two. In order to generate all the outgoing edges from a given paper, I define a function createedges which takes a paper ID and a list of references, and output a list of directed edges from the paper to its references. This is the code:

jsongraph = Import["cit_graph.json", "JSON"];

createedges[x_, y_] := DirectedEdge[x, #] & /@ y

listg = Transpose[{jsongraph[[All, 1]], jsongraph[[All, 2]]}];

listv = DeleteDuplicates[Flatten[listg]];

liste = DeleteDuplicates[

Flatten[createedges[#[[1]], #[[2]]] & /@ listg]];

gcites = Graph[listv, liste];

One can then call PageRankCentrality on the graph, after specifying the parameter alpha.

alpha=0.85;

Cg = PageRankCentrality[gcites, alpha];

result = Transpose[{VertexList[gcites], Cg}];

result = Prepend[result, {"PaperID", "pagerank"}];

Export["result.csv", result];

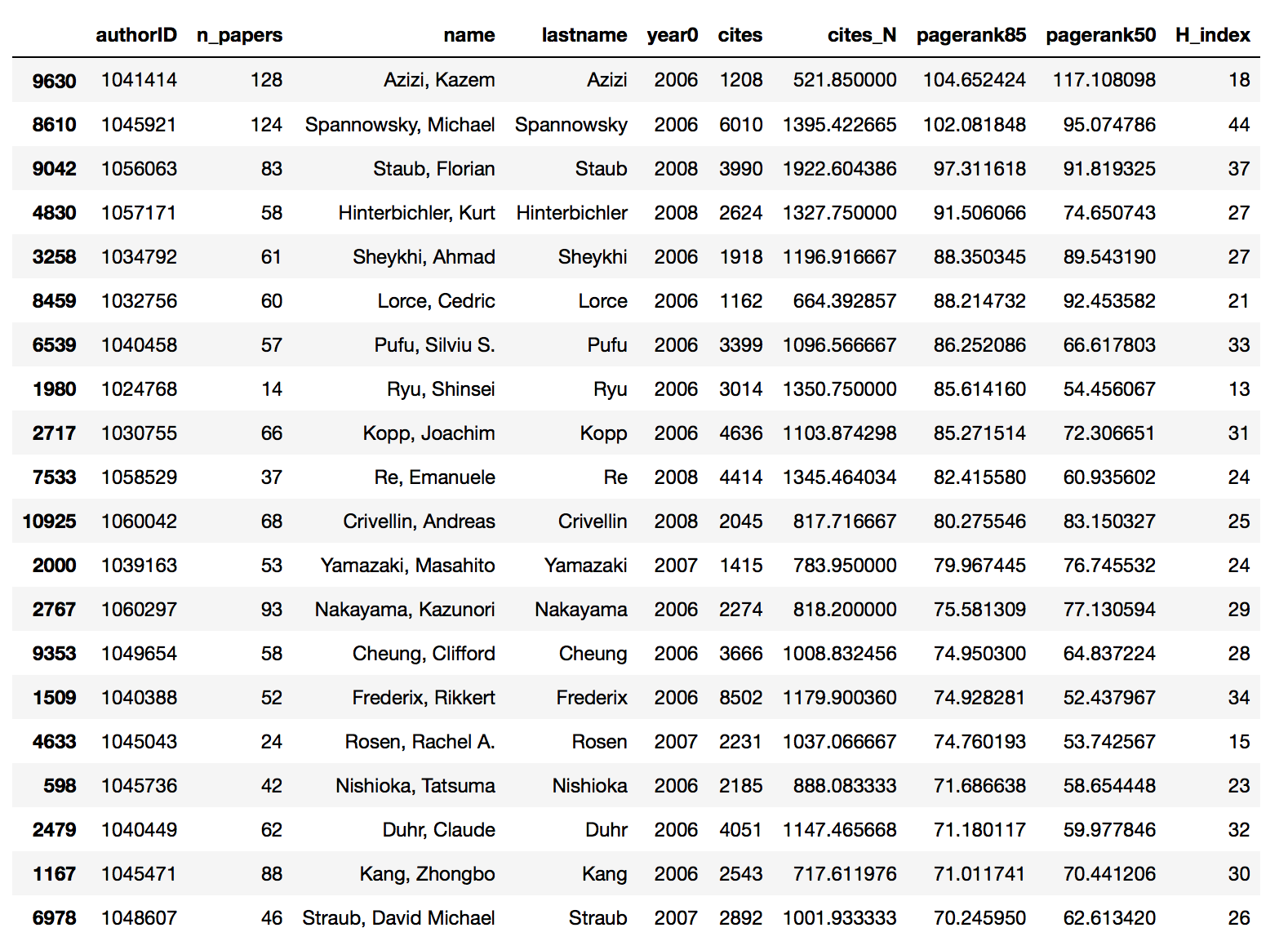

The results are then exported as a csv file, the first column being the paper ID and the second its PageRank. alpha=0.85 is the typical value used for web ranking. I will also use a smaller value alpha=0.5. All it takes now is to assign the normalized PageRank to every single author and BAM!, here are the results (I order them using alpha=0.85 and multiply all the scores by 1e5).

The global message is that PageRank is pretty consistent with the other bibliometric indices. This is not surprising as the first twenty entries all have pretty impressive records, regardless of the particular index used to evaluate them. Looking more in detail, you can see that the first entry according to PageRank matches with the first entry according to number of papers, while it was out of Top20 for the other indices. As already pointed out, many of his paper belong to nuclear physics rather than hep-ph or th. So this can lead to the anomalous behavior.

Conclusions

From a very personal standpoint this exercise did not really lead to any kind of ego boost. I never end up in the first 20, or in the first 50, nor, steadily, in the first 100. My place is in the first 150 for the majority of the indices. This is not awesome, but it isn’t bad either.

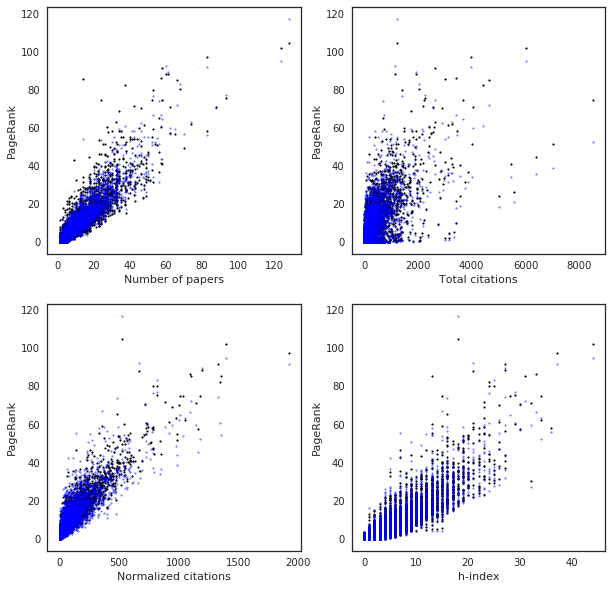

More on point, it is not surprising that all the classical indices agree in deciding the Top20. What is probably more surprising is that PageRank agrees with them too. One possible reason for this behavior is that in order for PageRank to become different than, say, citations, more time (in terms of paper being written) is needed. As the following figure show, PageRank is indeed very much correlated with the classical indices.

Am I surprised by the results? I’m not sure. I know personally many of the people in these Top20, I may have even written papers with some of them. So I obviously have my own opinions. This bibliographical classification is very partial. Apart from more technical details about the contribution of each author to a paper or the specific field of study, it is clear that the authors in any of these Top20 have awesome records. All the various bibliographical indices I have been looking at obviously favor authors who have done a lot of work. On the other hand there are very good physicists, with many ideas, but writing fewer papers and they end up being penalized by these ratings.

So take everything with a grain of salt, don’t be too happy, don’t be depressed, and in particular don’t be mad at me.