I talked about the arXiv in my previous post. If you are a theoretical phisicist and you write a paper you will post it there whenever it is ready. Everyday (Friday and Saturday excluded) at 8PM Eastern US Time the new papers of the day will appear on the website. Notice in also that the ‘X’ in arXiv is supposed to be a greek ‘chi’ so that arXiv is pronounced ‘archive’. The following is a screenshot of papers titles and abstracts from a random Friday.

If this sounds OK to you, nice, the trick worked. These are not real papers from the arXiv. They come from snarXiv. The snarXiv is able to generate plausible titles and abstracts for papers on hep-th that do not actually exist. It was built by a real physicist, David Simmons-Duffin, now assistant professor at Caltech. The snarXiv is built using so colled Context-Free Grammars (CFG). They are a set of recursion rules that can be used to generate strings with a specific pattern. Since most linguistic forms appearing in naural languages are context-free, given the right set of rules the generated strings will sound like reasonable abstracts.

The set of rules used by the snarXiv can be found here. You need to know about physics a little bit, or at least about how physics sounds, in order to compile this list of rules. I guess it also takes a lot of time to do the actual writing. On the other hand running snarXiv is very light on computer resources.

sNNarXiv

As we move toward the final and complete domination of the human race by artificial intelligences, one small project to pass away my remaining time as a free biological being is to build an alternative version of snarXiv using machine learning techniques. From now on I will refer to this attempt as sNNarXiv.

DISCLAIMER. As I am not a machine learning expert, I will end up using mostly off-the-shelf code (and probably old) written by others, with minor but important modification. I will try to keep track of all the simplification I am making and points where the discussion can be improved. I want to obtain something that works as fast as possible, leaving all the possible improvements to the future (perhaps infinitely far in time).

What I will try to do in practice is to have an algorithm which is capable of generating titles and abstracts sounding like those that you can read on the theoretical physics section of the arXiv, hep-th. Choosing hep-th and not another category is a conscious choice made to minimize the shortcomings of my algorithms. Hep-th papers contain more jargon and oddly-sounding words than other sections of the arXiv: even if my algorithm sucks, its results will suck a little less when applied to hep-th.

The technologies that I will need are those used in Natural Language Processing (NLP) in particular Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and distributed representations of words like Word2vec or GloVe.

Overview

What I will do in practice, is to train a RNN on the corpus made of titles and abstracts from hep-th, and then use such trained RNN to generate new samples. To be precise I will train two different RNNs, one for the titles and one for the abstract. This is, I believe, the main shortcoming of my procedure: in a given generated pair of title and abstract, the first will have no relation whatsoever with the second. One way to fix this would be to treat the pair (title, abstract) as a single unit. For some reason this was not working well given my time/computing resources. Another way would be to generate an abstract and then build an algorithm which is able to generate a title conditioning on that abstract. This looks quite complicated to me.

One of the most famous example of text generation using an RNN is the one in Andrej Karpathy’s blog, in which an RNN trained on the Shakespeare corpus is then used to generate new text character by character. This approach would be immediately exportable to the sNNarXiv. The problem is that it doesn’t work well. Maybe again because of limited time/computing resources the result that comes out trying to do this are not good. If the RNN is trained on sequences of characters, before being able to generate reasonable abstracts, it has to learn english syntax and the training become very long, probably too long given the limited size of the training set.

The strategy I will follow instead is to train the RNN on the sequence of words making the titles and abstracts. Since the number of unique words that will appear in the corpus that I will use is around 10k, it will be crucial to encode them using a distributed vector representation in order to reduce the dimension of the input space.

In the following I will describe the algorithm used to generate abstracts and briefly sketch the modification needed for the titles, as these are very minor.

The data

The data I will use for training are obtained from the Inspire database which I already used here. I will extract from it all abstracts and titles of papers corresponding to the hep-th category. There is a total of something less than 80 thousand abstracts and a total of 37 thousand unique words. This is a lot of unique words, so some preprocessing of the abstract is necessary.

Abstract can contain formulas and these can be particularly difficult to learn because the may display a lot of variations. Instead of trying to learn a formula I replace all formulas in one abstract with a special string, xxxxx, so that I will be able to substitute a formula whenever this special string appear after the abstracts are generated. Indentifying a formula can be complicated. In principle all inline math expressions in Latex are surrounded by $ signs. This command takes care of that

re.sub('\$.*?\$','xxxxx',abstract, flags=re.DOTALL)

Formulas of this kind are saved to a file, so that they can be substituted back later after generation is concluded.

Sometimes people just put their formulas with no $ signs in their abstract (don’t do that). In order to take care of that I define a set of standard characters

good_char=u'0123456789qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmQWERTYUIOPLKJHGFDSAZXCVBNM,.!?;:-‘’"/'

and I substitute with the special string xxxxx all words which contains characters other than good_chars. All words are also downcased and the special character # is added at the end of every abstract. Finally all abstracts containing words occurring less than 5 times are removed. There are also a few extra modification that I apply, as for instance modifying special unicode chars that sometimes appear or removing all text between parenthesis, that you can see on the notebook here). In the end I am left with order 50 thousand abstract and about 10 thousand unique words.

Similar massaging is done to the titles dataset. One main difference here is that titles containing formulas (as defined above) are dropped altogether.

Recurrent Neural Networks 101

A Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is a Neural Network adopting a particular parameter sharing framework suited to handling data with some kind of sequential structure. Using RNN to generate text is a very 2015 topic. There are plenty of blog posts on the subject (this is a great one ) and even books now. For this reason I feel I am allowed to streamline my discussion, without entering into too many details about recurrent nets.

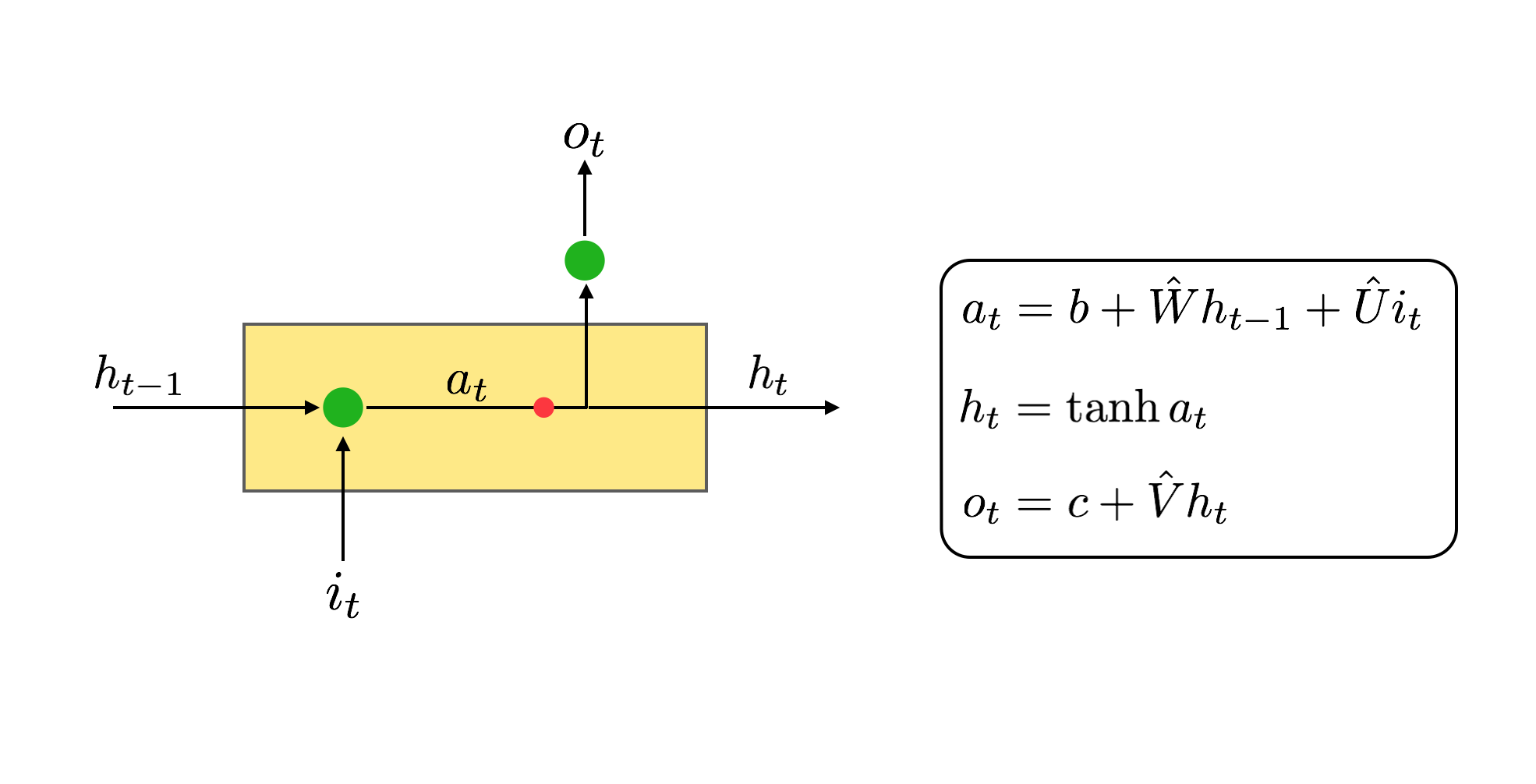

The basic unit of a RNN is the recurrent unit. A recurrent neuron, as every NN unit, has an input and an output. On top of these, a recurrent unit has a state. The state serves as a memory. What makes a recurrent unit recurrent is the fact that its output at time t, depends on the input at time t but also on the state of the unit at time t-1. See Figure 2 for the very simple math.

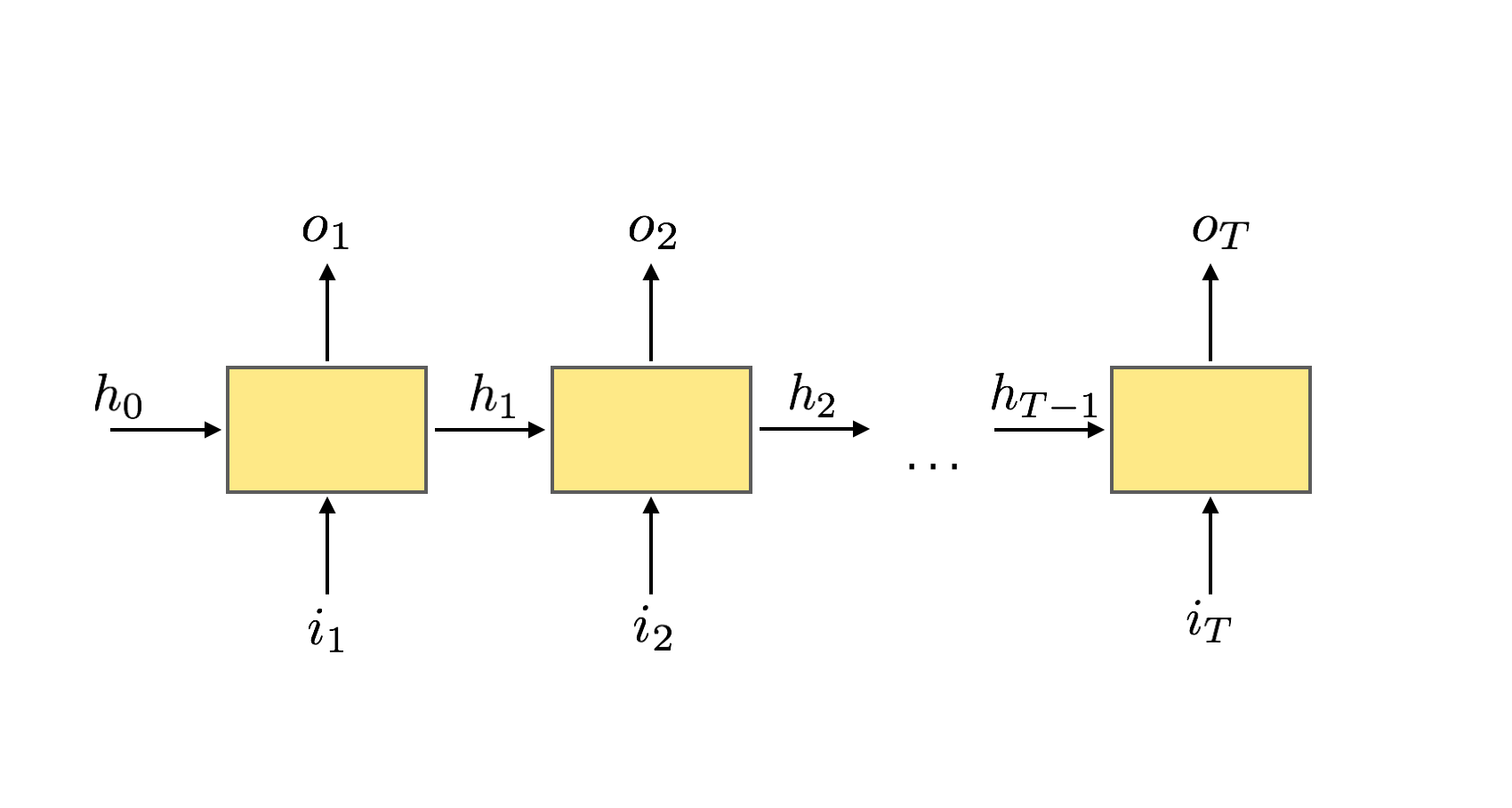

Such a non-local time dependence can be puzzling especially if one is trying to figure out how backpropagation is going to work. The trick is to fix a number T, an initial value for the hidden state, and unroll the RNN through T time steps. See Figure 3.

Such an unrolled RNN is just a standard neural network with weights which are shared among neurons. As for standard NN one can stack one recurrent unit on top of another to get a multilayer RNN.

One problem with these basic recurrent units is well known, and has to do with the poor way they are able to handle long term correlations in a sequence. When unrolled in time over several time steps, backpropagated gradients tend either to become extremely large or vanishingly small leading to either instabilities or no training. The solution to this is to replace the basic recurrent unit with special units like LSTM, GRU and so on. I am not gonna try to explain the way these work. If you code your RNN with something like TensorFlow, as I will do, you can just build your RNN using these special units instead of the basic recurrent ones. If you still want to know more, there are plenty of resources online. I suggest again this to start.

I am gonna be using GRU units in the RNN I will build: they are easier to understand than LSTM and they appear to work better with the problem at hand.

The job for the RNN I will build is the following. At time t the RNN will be fed the t-th word of an abstract (or title) and, given its hidden state, function of all previous words, will try to predict the t+1-th word.

Word embeddings

An important point to discuss is the way words are represented in the network. The size S of the vocabulary is of order 12k. A one-hot embedding of such a dimension would be extremely inefficient. The way to go is to pick a denser embedding, in which every word is represented by a vector in some lower dimensional space of dimension D.

In TensorFlow such data embeddings can be handled through the following commands:

embeddings = tf.get_variable('embedding_matrix', initializer=init_emb)

rnn_inputs = tf.nn.embedding_lookup(embeddings, x)

embeddings is a TF tensor of shape [S,D] containing the word embeddings, which are initialized to some value init_emb. The function tf.nn.embedding_lookup takes a tensor x of shape [d1,...,dn] (in this case it contains batched input data) and turns it into a tensor of shape [d1,...,dn,D] substituting to its entries the appropriate embeddings.

The embedding matrix can be understood as an affine transformation between the one-hot embedding space and the distributed one. embeddings is indeed a TF variable and as such its weigths will be updated during backpropagation. From this point of view it sounds as a good idea to initialize this variable not with a random embedding, but with one which already capture some of the statistical correlation in the corpus we are trying to learn.

The most famous algorithm to generate a vector embedding of words is probably Word2Vec. Word2Vec can capture approximate linear relationships between words and their meaning. One famous example of it is the fact that the vector representing king - man + woman is close to the one representing the word queen.

The Word2Vec embeddings can be downloaded and used. The problem with them is that the corpus I am interested in contains terms that the pre-trained Word2Vec probably have never seen, like AdS, renormalization, inflaton and so on. Luckily there is a very nice alternative to Word2Vec, that can produce word embeddings from a corpus of your choice, and that you can very easily train on your laptop. This is GloVe. To understand the difference between Word2Vec and GloVe I strongly recommend this Youtube lecture series by Richard Socher.

Using GloVe I train two different word embedding, one on the hep-th abstracts and one on the hep-th titles. The difference is the embdedding size, 512 for the former and 100 for the latter. These dimensions are also the dimensions of the hidden state of the relative RNN. A posteriori it is clear that a 512-dimensional word embedding is way too large, so if there is one single thing to update for the next sNNarxiv version, it would be this one.

Training and generation

Now to summarize. Two RNN are trained one for abstracts and one for titles. Both of them have two layers of GRU units and they are both unrolled through 30 times steps. The batch size is 32. The initial word embedding is obtaines as explained above. Both RNN are trained on a GPU for approximately 2 thousand epochs. This requires roughly 2 days of running. No particular testing is done: training is successful if I like the generated text.

So, how is text generated when the neural network is trained? Quite easily. Once the trained RNN is fed a word it will output probabilities for all the words in the dictionary. One can then pick a word at random among the N most probable ones, stick this word in the sequence and feed the sequence back to the RNN. And so on.

Two parameters playing an important role in generation are N and the RNN temperature. This latter parameter enters in the final softmax activation function which decides the probability for different words. A larger temperature makes the probability distribution more shallow. This is similar to the effect of a large temperature on an ensemble of states distributed according to the Boltzmann statistic. Choosing a small N or a too small temperature typically collapse the output of the RNN to a sequence of equal words. Not very interesting. During generation I will use N=8 and T=1.2.

Results

And finally some results. Once the abstracts and titles are generated by the RNN, a minor amount of massaging is necessary. Words occurring after a period are capitalized and some additional amount of capitalization is done ad-hoc. For instance if the word witten appears, it will be substituted by Witten. Similarly for other names or standard acronyms. Many of these operations can be automatized, but I didn’t do it yet.

Another important thing to do is to substitute formulas back to the abstracts. As mentioned above, all formulas have been collapsed to a special word xxxxx. After generation, everytime such a special token appears, it will be substituted with a formula picked at random among those saved during pre-processing.

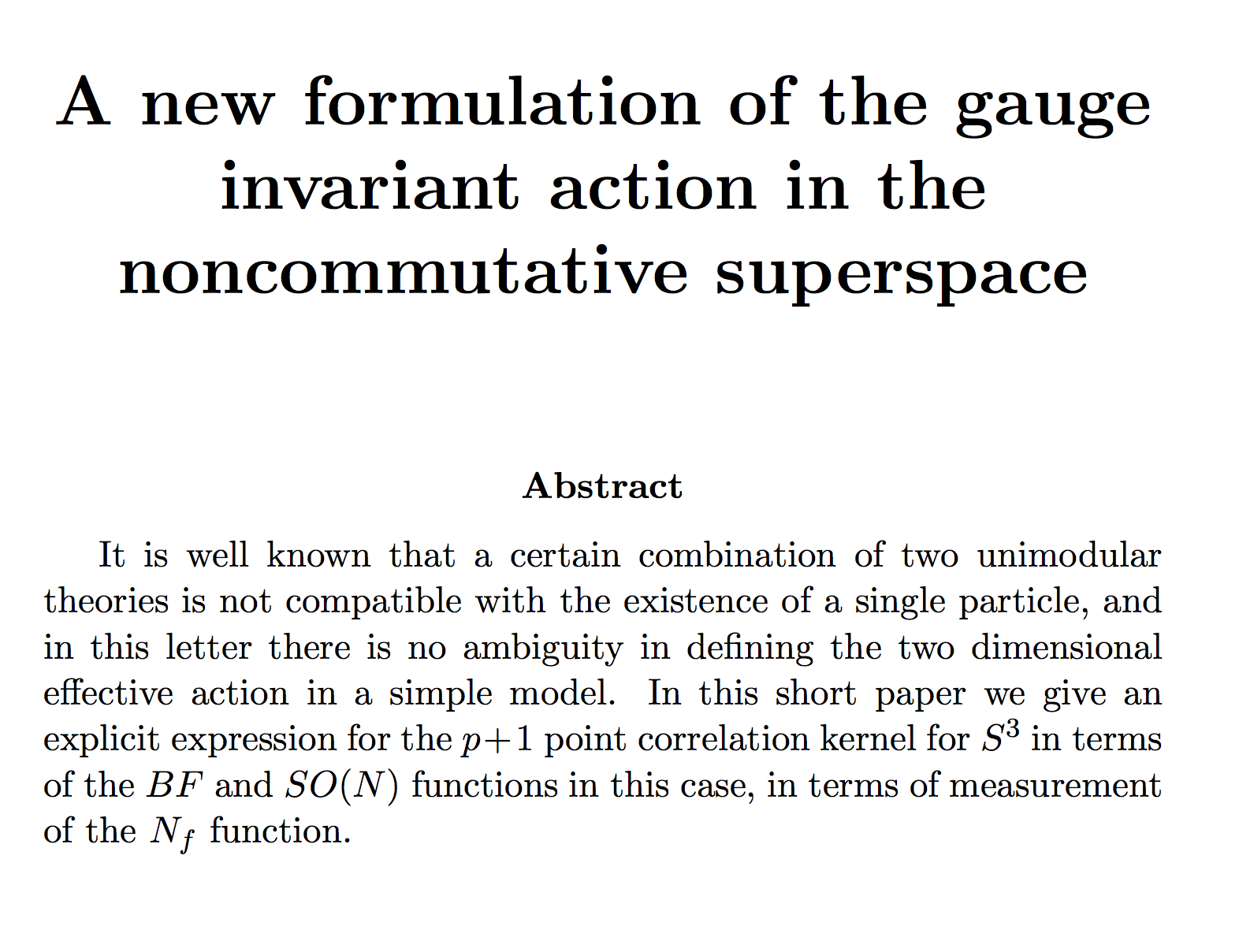

So here you are an example of what the RNN generates.

I believe that the results obtained by sNNarXiv are at least comparable to those generated by the snarXiv. Furthermore many improvement over this basic implementation are possible. As I already mentioned it would be great to find a way to generate titles conditioning on the abstract content.

Simpler adjustment are also possible; I believe that the he size of the abstract embedding is too large and reducing it would probably improve performances. Longer training would also be desirable. Finally it would be nice to generalize the sNNarXiv to other arXiv categories.

You can find all notebooks to train sNNarXiv and generate suff on my Github page. I also put there two files containing already generated titles and abstracts and a python file that picks two of them at random and spits a Tex file that, when compiled, reproduces the format shown in Figure 4.

Have fun!